In February 2020, I, along with 14 other people, arrived in Leeds to join the kick-off meeting for the MH-CREST project. It’s not first time I’ve taken part in a study advisory group, or indeed contributed to research on mental health crisis care, but as the project draws to a close, I’m keen to reflect on what I have learnt as a participant, and why co-creating knowledge is fundamental to humane and effective mental health care.

MH-CREST is an NIHR funded study which seeks to understand how community crisis care services for people with mental health problems work, who they work for, and in what circumstances. It is led by a team based in The School of Healthcare at the University of Leeds and sponsored by Sheffield Health and Social Care NHS Foundation Trust.

So back to that initial meeting, and the first thing I’m struck by is the presence of people with lived experience. By the time we’ve gone round the room, and excluding the research team, over half of those present are people who are using, have used mental health crisis services, or are carers for people who use mental health services, with the rest of the group made up of mental health professionals, commissioners, policy makers, and researchers. It isn’t just the balance of lived experience, it’s also having a diversity of experience. This includes people from different cultural backgrounds, people currently using crisis services, people involved in service provision from a position of lived experience, and people who have had long-term experience of mental health services including crisis care. In part this has been achieved by reaching out and collaborating with local crisis services, so that people in their early stages of recovery are able to contribute with support from staff and keyworkers. But is also a marker of the commitment to lived experience and the approach the research team have taken including making the research accessible in terms of what we are doing and ensuring that people feel supported as part of this.

MH-CREST combines evidence synthesis with realist methodology. What that means in practice is that the team are effectively seeking to address their research questions using published research on mental health crisis care. But the areas they focus on, and their understanding and interpretation of the literature and findings is informed by an independent advisory group (that’s us, outlined above). Co-design by nature is collaborative, but balancing different voices, diverse experiences and lived experience with notions of established knowledge can be tricky. One way they achieved this was by engaging us in common tasks – such as the diamond ranking task in the initial session. As my group huddled round the notion of ‘access’, seeking to understand its parameters and priority against other factors, we each shared our own individual experiences and knowledge – of accessing care in a crisis, being that member of staff at the end of the line, of commissioning services. I noticed how the process of knowledge creation became generative rather than cumulative, accepting and knitting together our common and different realities, rather than presenting them in isolation and opposition.

The meetings of the advisory group and our work together is perhaps the first time I’ve heard these different perspectives on crisis services voiced in the same room. However, of these it is the commonality of traumatic experiences that has stuck in my mind. Anyone who has been involved in mental health will have at some point listened to an individual recount their traumatic experiences of care. Fraught with emotion, they can be difficult to hear, and lead those in the room to question how unique or timely those experiences were. What I heard in the room, were how common traumatic experiences of seeking help are both in the past and present. This included what can only be described as systematic failings of care, to responses which were experienced as unhelpful or invalidating at a point when an individual felt at their most vulnerable and distressed. The consequence we heard is a growing mistrust of mental health services and a reluctance to seek help on future occasions.

And yet so many of us need and at times are dependent on that care. When I joined the first MH-CREST meeting, I did so largely as a policy researcher who has followed and written about provision of mental health care. But as the country was plunged into a series of lockdowns in response to the spread of Covid-19, my life became increasingly dominated by my own mental illness and I too had to consider whether to seek help in a crisis and the response that I would receive.

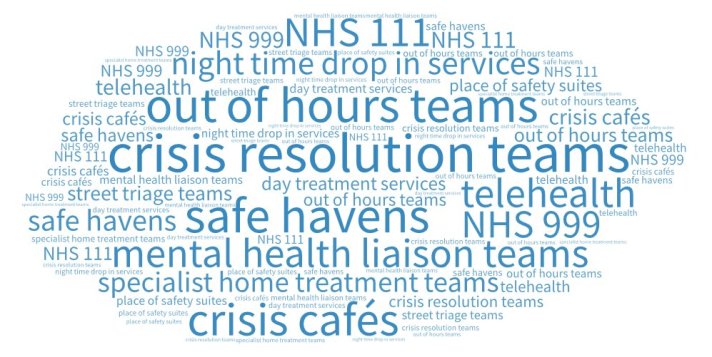

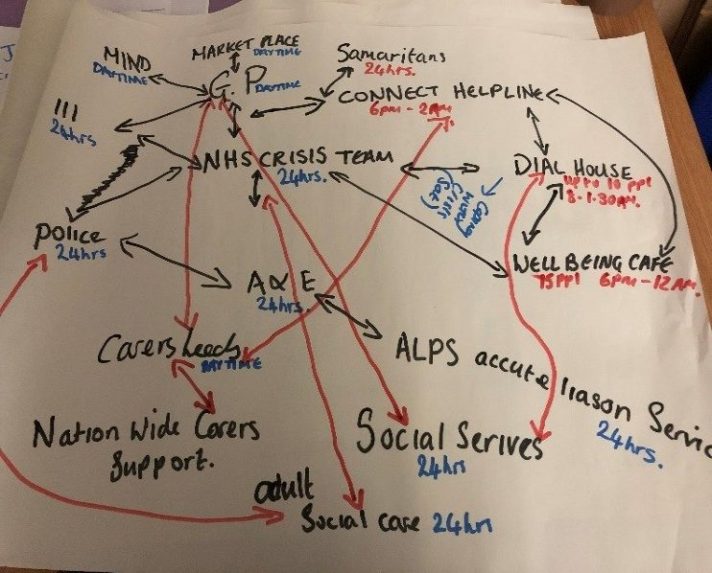

Over many years there has been an increasing focus and investment in services for people experiencing a mental health crisis. On the ground there has been a proliferation of services, from crisis intervention and home treatment teams, to street triage, crisis café’s and most recently NHS crisis lines. And yet, we know that providing a means to access services in a crisis isn’t enough – staff and services are often constrained in the response they are required or able to give, and not everyone who experiences a mental health crisis will access care. Our work as part of MH-CREST has shown that no one service is likely to work for everyone, but where prioritisation of a few common features of services identified through the collaborative work of the group and supported by the evidence have the potential to improve the acceptability and effectiveness of the crisis response provided to people in distress.

Helen Gilburt

Fellow in Health Policy, The King’s Fund

To keep up to date with MH-CREST follow the hashtag #MHCrest and the project PI Nicola on Twitter @UniLeedsMH using the hashtag #MHCrest.

This study is funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) HS&DR programme (project reference NIHR127709). The views expressed are those of the author(s) and not necessarily those of the NIHR or the Department of Health and Social Care.